Written by Raeesah Hayatudin

The Handmaid’s Tale

Author: Margaret Wood

Publisher: McClelland & Stewart, 1985

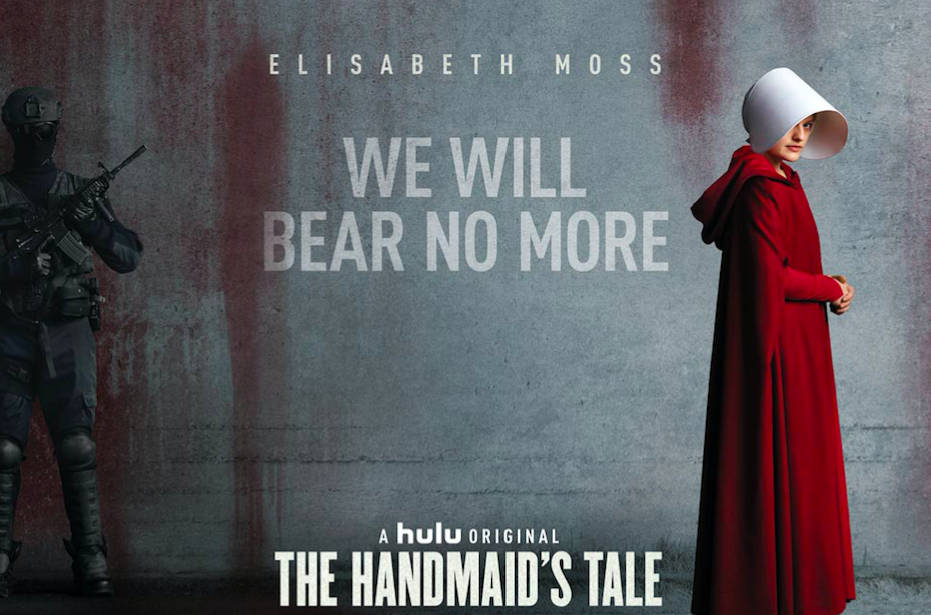

Before settling in to watch the first season of the recent TV show The Handmaid’s Tale from Hulu, based on the novel from Margaret Atwood, I hurried to reread the memorable book. And I was reminded of exactly why I loved this book so much, despite the painful story told by the narrator and the disturbing nature of the world within it.

Set in the dystopian world of Republic of Gilead (which was once the United States of America), the narrator, Offred, is a handmaid, a class of women in service to the “Commanders” – who are the men of the dominating class in Gilead – for reproductive purposes. The name itself, “Offred”, is a patronymic; it means “Of Fred”, Fred being the name of the Commander she is assigned to. This world is one in which most people are sterile due to sexually-transmitted diseases and pollution, and the handmaids are the only women remaining capable of bearing children. There is a certain hierarchy in Gilead where all men and all women are segregated into different classes; the status of a woman according to her class is signified by the colour of her clothing. For example, the handmaids are dressed in red and wear a white bonnet.

Through Offred’s flashbacks we understand part of the social and political decline of the USA which led to Gilead’s genesis. Atwood has said in an interview regarding The Handmaid’s Tale, “This is a book about what happens when certain casually held attitudes about women are taken to their logical conclusions.” Offred is a sympathetic character; we identify with her narrative voice, and we feel her pain. She could be any one of us, or someone close to us, really, and if we lived in Gilead her experience could be ours – and that’s one of the scariest aspects of this novel.

Is The Handmaid’s Tale a cautionary one? Yes, and it’s not just a warning about what could happen if misogynistic attitudes are taken to their extremes. It’s also a warning about how perilous it can be if power lies in the hands of dangerous people. The dynamic between Offred and the Commander, and that between Offred and the Commander’s wife, and several other relationships, are the result of the detrimental effects of how power affects the way people think and act. But the whole concept of power being in the wrong hands is also related to most gender issues today, and so, when we talk about issues such as women’s reproductive autonomy, also deeply involved in that conversation is the discussion of those who have the power to make decisions that affect everyone.

A striking feature of this book is the style of its narrative. I admire how Atwood uses masterfully written prose to express Offred’s thoughts and write her experiences, and to flesh out her development through the book. Atwood’s writing is rather poetic, and it’s very deliberate – each word is chosen carefully, used to arouse a particular feeling in the reader. Atwood expresses Offred’s pain effectively, and many of Offred’s thoughts in her private moments are deeply moving and almost agonizingly honest.

“I wish this story were different. I wish it were more civilized. I wish it showed me in a better light […] I wish it had more shape. I wish it were about love, or about sudden realizations important to one’s life, or even about sunsets, birds, rainstorms, or snow.

[…]

“I’m sorry there is so much pain in this story. I’m sorry it’s in fragments, like a body caught in crossfire or pulled apart by force. But there is nothing I can do to change it.”

There are other moments in this book which are very precious because they are full of life – Offred’s life, as oppressed as it is. Offred still manages to find moments that are her own even as she lives a life which is rigidly controlled, even as she lives a life where she does not possess agency over her own body. In this way, in our minds, Offred becomes someone real to us, someone almost tangible; someone we can connect to. This says something about Offred – the fact that she’s still able to find hope even in her situation means that her spirit is not yet broken.

“I want to see what can be seen, of him, take him in, memorize him, save him up so I can live on the image, later.”

The Handmaid’s Tale is a narrative of a traumatized woman. A woman who is relatable, and also very brave in wishing to tell her story, in her own words. It’s a way of taking control of her experience in the only way she’s able to have any control at all. I find it very interesting, the idea of telling your own story as a legitimate way of coping with a terrible experience, as a way of not being alone and as a way to attempt to reach out to others.

“But I keep on going with this sad and hungry and sordid, this limping and mutilated story, because after all I want you to hear it, as I will hear yours too if I ever get the chance, if I meet you or you escape, in the future or in heaven or in prison or underground, some other place. What they have in common is that they’re not here. By telling you anything at all I’m at least believing in you, I believe you’re there, I believe you into being. Because I’m telling you this story I will your existence. I tell, therefore you are.”

So, I urge you to give this book a read (or a reread), especially if you’re about to watch Season 2 of The Handmaid’s Tale in April 2018! I certainly can’t wait – season 1 was a great watch, and is mostly loyal to the book’s events.