Written by: Fajar binti Benjamin

Do you remember? Only last year, we were glued to our Twitter feeds, picking apart every new article, talking about it with our friends at mamak shops and hipster cafes alike, smirking whenever our lecturers not-so-subtly alluded to their own thoughts and opinions while trying to stay professional. It was the only topic on our minds. The GE14. History was made on the night of the 9th of May. For the first time since we established ourselves as a democracy, the opposition won and Pakatan Harapan stepped up as our official federal government.

The entire Malaysia was involved that night with 82.32% of eligible voters turning up despite a series of suspicious inconveniences that sprung up for oversea voters and the early closing of local voting centers. It seems every man and woman of age was involved, yet one place in the rabble was glaringly empty.

Where were the students?

The Universities and University Colleges Act bars students from being involved in politics. Established in 1971 after citing student activism as the main cause for violent outbursts like May 13, the UUCA in its original form restricted students from even voicing criticisms towards the government, let alone joining political parties or hosting political discussions. Amendments in 2012 loosened the laws somewhat to grant students freedom of speech as long as they were off campus and not affiliating themselves with their institutions.

Even with the amendments, we’ve still lost generations of reform and progress to this act.

However, it wasn’t always like this. Before the act was established in 1971, local public universities were a hotspot for political discourse. Discussion was not confined to private quips in empty classrooms, but was instead delegated real power and influence.

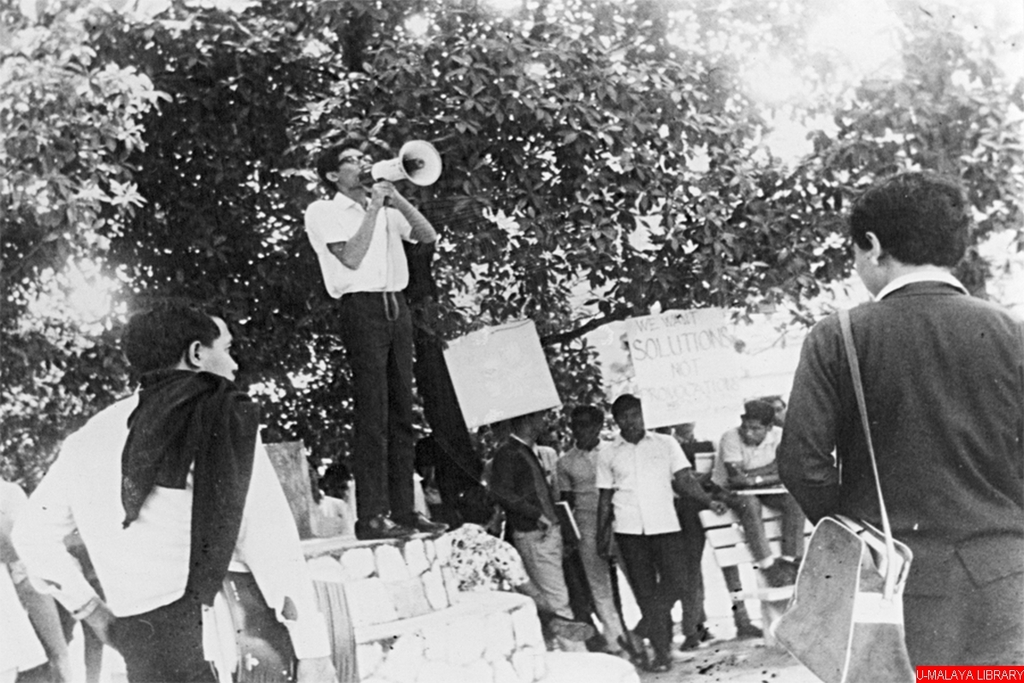

The then-infamous Speaker’s Corner of University Malaya was a delegated area for weekly talks and debates regarding any and every topic. “The students would debate anything from student representation in the university administration to the problems faced by the Malay peasantry. They would criticise anyone from the prime minister to the students’ union itself. Economy, race, religion – nothing was too “sensitive” for the students.” – Fahmi Reza, an artist-filmmaker who’s charted the history of the student movement in Malaysia.

The History

For my research for this article, I read the book Student Activism in Malaysia: Crucible, Mirror, Sideshow along with several other articles that will be listed at the end of this article and I managed to put together a brief and overly simplified timeline (excluding the issue of UM being split into two after the separation of Malaysia and Singapore).

1950s – UM’s Socialist Club established a newsletter named Fajar. This newsletter contained mostly articles criticising the British government and explaining socialist ideology. After being arrested in 1954 by British colonists in the first sedition trial of Malaya, Fajar’s editorial board (the Fajar Eight) were acquitted. By 1963, the newsletter was shut down for being too controversial.

1960s – Worldwide, students were causing change. In Paris, the largest strike in history organised by students working with trade unions almost toppled the oppressive government. Anti-war sentiment championed by students from the US and Europe was planted through protests against the Vietnam War. Everywhere, students were making waves. And students in Malaysia weren’t exempt from this movement. Of course, the newly-formed government wasn’t happy about this.

1966 – Speaker’s Corner was established. Politicians from both sides of the divide were invited to talk. Debates happened every Sunday morning.

1969, pre-elections – Students, under the authority of the UMSU (University Malaya Student Union) published their own left-leaning independent manifesto calling for basic improvements such as equal access to healthcare for all. This manifesto was meant to challenge whichever party that won to take up these causes. Instead, it simply stoked the ire of the coalition in power.

1971 – The UUCA was established. However, the UMSU found a loophole in the act and continued on as the only champion in student activism, being particularly outspoken about the lack of government intervention regarding rural poverty.

1974 – Everything came to a head when the UMSU was called to intervene as squatters (the homeless population) were being evicted from a settlement in Tasek Utara, Johor. They hopped into a school bus and made their way to the site, arriving just in time to protest the demolition of the site.

The government had had enough. Make no mistake, there was also a fair share of corruption and other complications that incentivised the government to shut down the voices of university students.

UM was shut down and rebooted with student activism wiped out like a virus. Speaker’s Corner was gone. The University Malaya Student Union was replaced with a Student Representative Council. The Socialist Club? Gone. The campus publication, Suara Mahasiswa, was also replaced with something more palatable.

Autonomy was completely removed from students. Every event and article had to earn a stamp of approval from the Vice Chancellor before it could happen. Pictures of student heroes of the past were torn down, their accomplishments erased from history books, clubs defunded, semesters compressed and shortened to give students less leisurely time for activism and so on.

Not only were students forbidden from participation, they were psychologically manipulated to stay away from it. This quote from the Information Minister at the time neatly sums up the overall sentiment: “The enemies of the country will always look for opportunities to weaken us, and the students will always be their main target”.

Whenever students were involved in demonstrations or expressed opinions of any sort, the narrative was always, “they’ve been manipulated by outside forces”. Students were given no agency or credit, basically treated like toddlers who don’t know any better than to throw a tantrum. This constant undermining led to the same passivity that the same generation who suppressed us, likes to complain about today.

The Question Now

Bad blood set aside, should students once again be granted access to politics?

There are arguments from both sides of the divide. After all, to some the ban was put in place in the first place due to the activism becoming incredibly tense, divisive and toxic. To others, it came about as a result of corrupt officials wishing to not be questioned and challenged at every turn. It’s all a matter of who you ask.

There is also an argument over the very nature of university. Is it simply a glorified school, a place where young adults become self-sufficient degree holders, or is it something more? Perhaps a place where intellectuals and activists are born? Many universities like to advertise themselves as places where the leaders of tomorrow are born, but leadership in what? Of a country we’re not allowed to speak of except with rose-tinted glasses?

And then there is the matter of, are our students mature enough to be trusted? A very real concern is that allowing politics back on campus would simply enable students to become targets of extremism and manipulation. It takes very little to plant an idea in someone’s head, and young people in general are more susceptible to jump aboard a cause without putting enough critical thinking or research into it beforehand.

Radical change is not always good. Just as students would be empowered to protest against corruption or for equality, they would also be allowed to espouse more divisive issues or dive towards extremism. Religion and race play enormous roles in politics, as little as anyone likes to admit it. What happens when the relatively peaceful atmosphere on campus is shattered by differing opinions being thrown about?

I get it, you know – politics are an ugly, divisive game. It brings out the worst in us, the stubborn creature too entranced by the perspectives that resonate most with its understanding of the world, to see truth shoved before its face. But I would argue that in our current political climate, it is too easy for people to shut their doors and dine with like-minded people. What bringing politics back on campus would do is fling those doors open and bring about a conversation where all sides could see each other clearly in the daylight, without bias or anonymity.

To read about the fiery antics of our grandparents’ generation is an eye-opener. They were the heroes and protectors of those who didn’t have the resources or words to protect themselves. A good chunk of them were studying on scholarships, and they recognised the debt they owed to society – which they repaid by pushing the boundaries and doing their best to improve the lives of the communities around them.

The concern about radicalisation is real and potent. Back in the 1960s, much of student activism was passionate, bordering on violent, conceitful and uncontrolled. The attitude of the average student in this day and age is the polar opposite. Complacent in their comforts and not particularly bothered by the institutionalised suffering so many across our nation suffer from.

Neither end of the spectrum is desirable. Perhaps instead, we can strike a balance, trusting students to use their freedom of speech with gravity and competence.

The Future

Good news! Our Education Minister, Dr. Maszlee Malik has updated us on his progress in setting our voices free. The abolishment of the UUCA was on Pakatan Harapan’s manifesto last year and the act should be done and dusted by next year.

While we wait for that to happen though, we should educate ourselves to the best of our ability. Go beyond reading headlines on Twitter – click through to the article. Determine which sources can be trusted to be impartial. Read our history for yourself; the entire Malaysiana section in the library is waiting for you to simply put in the effort. Below I’ve included a list of books that may be found in the library as well as several links to good articles.

More importantly, figure out which causes you want to champion. There is no shortage of stances we must take up. Global warming, child marriage, the human rights violations happening everywhere from Myanmar to China to Palestine and the ever worsening wealth disparities. We are going to someday inherit all these problems.

As Martin Luther King once stated to the students protesting the Vietnam War: “You, in a real sense, have been the conscience of the academic community and our nation’’, and so must we become the conscience of the world.

Books in the Sunway library:

- Letters to Home

- Peninsula

- Masharakat Melawan Mahasiswa

- Student Activism in Malaysia: Crucible, Mirror, Sideshow

- Alamak! : all in God’s name

Articles:

- Undergraduates Are The Voice of The People – The Nut Graph

- Student Activism: The Struggle Continues – The Nut Graph

- UM Students Become Trailblazers of Democracy – New Straits Times

- Speaker’s Corner Back at UM – The Star

- The Justification for the UUCA – Loyar Burok