Written by Samantha Chang

In the age of hipsters and Keala Settle’s catchy new hit, we won’t be running out of reminders for us to be true to ourselves anytime soon. The idea is not a novel one: from Nietzsche to Camp Rock, the message has been reiterated throughout the ages – and quite deservedly too, as it’s a fundamentally positive message. However, we run the risk of spoiling ourselves sick with it and turning it into a cliché, and the danger of turning a good message into a cliché is that it loses its meaning.

Declarative statements such as “just be yourself!” and “this is me” are like simple carbs: easily enjoyed and digested, but nutritionally empty. I find that being authentic is not a final, transcendent psychological state that you reach once and achieve forever – rather, it’s a balancing act that requires constant upkeep and keen social and self-awareness; in other words, it’s hard work. Which could be why most of us comply with norms unthinkingly: not out of ignorance, as commonly believed, but out of fear, fatigue and convenience – as explained by writer Ralph Waldo Emerson, “It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

So why is it that the struggle between self and society seems to be such a contentious and universal one? How do we walk the tightrope that separates normal from abnormal social behavior? More importantly, where do we draw that line?

The myth of normalcy

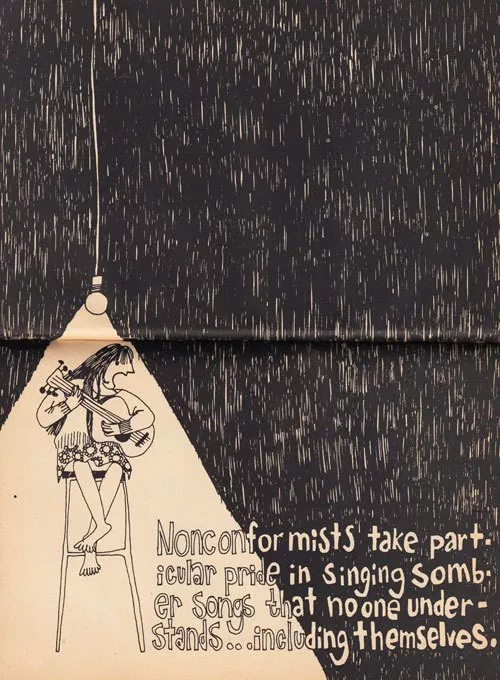

None of us, I think, are spared from that niggling suspicion at the back of our minds that we’re really just quite weird – more so than others. We all want to be on the ‘right side of normal’, and we can probably call to mind a few examples of some acquaintances whom we think could use an extra dose of conformity – you know, just . . . for their own good.

Source

Conformity is a thing for a reason, of course: evolutionary psychologists believe conformity and all the feelings that come with it – shame, self-consciousness and guilt – are central to fostering prosocial behaviour and cooperative relationships, which have helped us to survive. As put by Fessler, “When efforts, energy, and knowledge are pooled, the results are often not merely additive, but multiplicative”, which is why we reward group-beneficial actions and punish self-interested actions (like that one slacker groupmate you still hold a grudge against till this day).

But similarly, variances in personality traits are healthy and play an equally important role in our evolution as a species. Yale clinical psychologist Avram Holmes argues that “Any behavior is neither solely negative or solely positive. There are potential benefits for both, depending on the context you’re placed in.” So if you’re anything like me and you have a tendency to be more emotionally unstable than the average Joe, it’s not all bad news: your debilitating anxiety helps you to anticipate threats more readily, and by extension, increases your odds of survival.

The study however, argues that our personality traits can be considered unhealthy if they impair our ability to function in our immediate contexts. That said, there are plenty of eccentricities we shun that aren’t even near that extreme at all. Why do we bind ourselves to these rules then, if they are seemingly harmless?

Cultural differences

If you are Malaysian, then you are most probably abnormal – at least, in the eyes of another Malaysian. We live in such a culturally complex and diverse country that a single basic prototype of an ‘average Malaysian’ simply does not exist. Forget race: even within races, we’re further divided into subgroups based on language, religion, socioeconomic level, generation, family life, individual experiences – all of which construct the way we perceive reality.

Like the numbers on a padlock, the combinations are virtually endless. And all these identities that you hold in you won’t always weave up seamlessly together; they threaten to contradict each other all the time – for example, if you are both gay and religious. Now, due to globalization, we live in a constant state of tension with ourselves, we wade in the grey areas between one identity and the next – and we do it quite comfortably and happily. Malaysians have made our weird the norm, and we’re even proud of it.

My own identity conflict is very common: I’m Chinese, but I can’t speak Mandarin or any of its dialects. As English is my first language, I naturally sought out American and British media growing up. As a result, I unintentionally started to model myself after the characters I read about and watched, who were primarily white and western. This phenomenon is highlighted in this study, which explains that when we identify with media characters, we live vicariously through their experiences, and due to that, we assume their identities and lose our own. The consequence of that – other than the fact that I was an eight-year-old with a worryingly vivid knowledge of fifties England – is that I grew up constantly torn between Western norms and values (which I had internalised) and local ones. I’m always made painfully aware of this fact whenever I have to visit relatives as there is a clear communication gap.

Because cultural norms can vary so widely, many people are starting to believe that what we think of as ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, socially acceptable or morally permissible is unavoidably ethnocentric in nature – that is, evaluated through the standards of the culture in which we grew up – and that there is no universal ‘normal’ or ‘good’. This is known as cultural and moral relativism. Relativism is usually contrasted with absolutism, which is the view that some values are universal and have objective value judgments. The nature of social constructs is a topic of hot debate today, particularly in politics and philosophy.

While the big minds of today battle it out on the big questions and their implications for society as a whole, the rest of us are still stuck with the dilemma on an individual level. We know that we still feel the need to connect to others, but doing so at the expense of self-expression hurts. So, what now?

Connecting to Others by Connecting to Yourself: A Hypothesis

“[If you genuinely listen to someone], they will tell you the weirdest bloody thing – so fast. So if you’re having a conversation with someone and it’s dull? […] You’re not listening to them properly, because they’re weird, they’re like . . . wombats, or albatrosses or rhinoceroses or something – they’re strange creatures.” – Dr. Jordan Peterson

We all know the benefits of individuality: when we’re not inhibited by self-censorship, we have more space to be creative thinkers and have more courage to have difficult, intelligent discourse, which opens up more social and economic opportunities for us. But the threat of alienation makes us hesitate: think of a time when you didn’t raise your hand although you knew the answer for fear of looking stupid, or when you outwardly agreed with someone but inwardly didn’t believe in your words.

Our specific combination of identities and experiences that make us who we are may be so unique that it can feel isolating at times, but the secret we all share is that we’re all odd one way or another. Our private selves emerge when we have time to retreat from watchful gazes, and it’s during these times we know intuitively who we actually are. And, being “true to our own solitude, true to our own secret knowledge” as Seamus Heaney puts it, is what “links us most vitally and keeps us most reliably connected to one another.”

And if you think about it, it makes sense. When you allow yourself room to be candid in your interactions with others, you are implicitly letting them know that you trust them and that you won’t be too quick to judge their eccentricities as well, which leads to a feeling of safety and in turn, more genuine interactions. Furthermore, acknowledging and accepting your idiosyncrasies makes you more forgiving of others’ oddities too; you start to see them in a more holistic light: not as their social roles, or who they want you to think they are, or who they are in relation to who you are – instead, as who they actually are, in all their faulty, wonderful glory.

That being said, it’s not always possible to find a common ground with everyone – and that’s okay. There are always other like-minded people around, if you care enough to look.